In this story:

In February 2022, as the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion pursued a contentious restructuring plan that would close its 150-year-old rabbinical school in Cincinnati, the college administration offered a new vision for the campus here.

“We seek to make Cincinnati a hub for vibrant learning and community building year-round,” said a white paper about the restructuring, offering alternative program ideas like an online, low-residency clergy school with occasional in-person gatherings in Cincinnati.

“We hear cantorial students leading worship in the Scheuer Chapel, and hallways humming with conversations as rabbinical students explore new ideas and grapple with age-old controversies,” the document said.

Later in April, spurred by financial issues, the HUC-JIR Board of Governors approved the restructuring, leaving intact the college’s three other rabbinical programs in Los Angeles, New York City, and Jerusalem. As part of the restructuring, the low-residency clergy program is supposed to launch by 2025, and the Cincinnati rabbinical school will be closed by 2026.

In the two years since that vote, Cincinnati has seen a few new HUC-JIR programs, including an alumni study retreat and a week-long learning intensive. The low-residency clergy program is still early in development, with the college advertising on social media – then deleting the advertisements – for a mid-March informational session.

But those programs don’t make up for a campus that students, alumni, and former faculty describe as now being in hospice, with the community helpless and exhausted as HUC-JIR offers little substantial detail, in public or private, to explain how the institution will achieve its glowing vision for 3101 Clifton Ave.

Instead, the campus is being hollowed out. The administration offered buyouts, pushed out faculty and staff, and slated more programs for closing – including its 76-year-old graduate school in Cincinnati. “Leave us alone and let us die in peace,” is a common refrain among some Cincinnati students when discussing the college administration.

“There’s a feeling of trying to keep things going, but also, you kind of wonder how long the fuel lasts,” said one Cincinnati student, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation. “The fear is, what else will the administration do to expedite this process?”

The administration is also experiencing a staff exodus that includes Amy Goldberg, the college’s chief financial officer, and Yoram Bitton, formerly the national director of libraries.

Bitton resigned in early 2024 because of alleged pressure to sell rare books from the collections of the Cincinnati Klau Library, one of the premiere Jewish libraries in the world. In mid-March, senior Judaica specialists from the auction house Sotheby’s spent several days evaluating the Klau’s holdings. Warned of budget cuts, Klau staff are now anticipating layoffs.

Bitton declined to comment when reached by Cincy Jewfolk.

“I felt, and still feel, the worst for our professors and staff who have had to bear the brunt of this, who have had to support us through this…whose life work is going out the window,” said an alum of the Cincinnati rabbinical school, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation.

By 2026, absent full-time students, there will be few “hallways humming with conversations,” and remaining faculty will be reduced to only teaching virtually – a far cry from the tight-knit and vibrant in-person atmosphere that used to be a hallmark of Cincinnati. Without full-time academic programs, Cincinnati stakeholders see little reason for HUC-JIR to preserve the campus and its institutions.

Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who founded the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati in 1875 (Wikimedia Commons)

As many community members see it, this is a shameful and insulting end to a beloved – if deeply flawed – rabbinical school. The college is the legacy of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, a founding father of American Reform Judaism, who created the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to train rabbis with the academic rigor of higher education. HUC-JIR is the only rabbinical school associated with the Reform movement, and for most of its existence, Cincinnati was the flagship program and campus.

Over the course of 150 years, the college became the oldest and largest non-Orthodox rabbinical school in the world, and helped propel a number of academic fields, from biblical archeology to the study of American Jewish history.

While playing a key role in the evolution of American Jewish life, the college was also a cornerstone of Cincinnati, its Jewish community, and Jewish life across the middle of the country. Generations of HUC-JIR rabbinical students served Cincinnati, and likewise, generations of Cincinnatians were involved in sustaining the campus here.

“The decision to close this campus broke my heart,” said Dr. Gary Zola, the former executive director of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. Zola is a longtime tenured senior member of the Cincinnati faculty who decided to retire after the HUC-JIR board voted to close the rabbinical school.

“I am brought to tears when I think that in a year and a half, [the Scheuer Chapel] will sit dormant,” he said, “and there will no longer be rabbinical or graduate students studying daily in that iconic classroom building.”

‘Crushing’ deficits and fundraising woes

Meanwhile, HUC-JIR’s bet on financial sustainability through restructuring is not going well, a situation that may hamstring new programs and initiatives.

Since 2020, the college administration has said that it faces regular deficits – in part because donors allegedly don’t want to give to an institution stretched across three stateside campuses (and a fourth in Jerusalem) with duplicated programs and staffing. Closing the Cincinnati rabbinical school was meant to entice donors back to the table.

Instead, public audits show that HUC-JIR’s fiscal year 2023 (ending June 30) was the college’s worst since the Great Recession.

The college has two main kinds of operating revenue: funds restricted by donors to specific programs or uses, and unrestricted funds, which make up the college’s budget and cover its operating expenses. HUC-JIR’s operating expenses are roughly $43 million a year.

One way to understand HUC-JIR’s finances is to subtract operating expenses from unrestricted revenue. If expenses are greater than unrestricted revenue, that indicates an operating shortfall – in other words, that the college is lacking money to pay for its core activities.

In fiscal year 2009, HUC-JIR’s worst year in the Great Recession, financial information published by the college showed an operating shortfall of nearly $8 million. In 2023, public audits show the college’s shortfall was more than double that, at $16.5 million.

Contributing to the shortfall is a severe decline in HUC-JIR’s fundraising.

Annual contribution revenue, which measures gifts and pledges for future giving to the college, fell by nearly $2 million in 2023 from the previous year – reaching its lowest level, at $11.5 million, over the nine years tracked by HUC-JIR’s audits.

At the same time, cash flow statements, which track how much money is actually brought in (rather than promised or pledged) in a given year, reported that contributions to HUC-JIR dropped from $10.2 million in 2022, to $5.2 million in 2023.

Compared to pre-pandemic fundraising, that’s a roughly 70% decline: From 2015-19, the college regularly brought in between $15 million-$20 million annually in cash from contributions.

“If the contribution revenue is declining, but cash from contributions is declining faster, then I would say they’re having two issues there,” said Brian Mittendorf, a professor of accounting at Ohio State University who looked over HUC-JIR’s audits at the request of Cincy Jewfolk. “They’re having less success raising [long-term] funds. And…they’re having even less success raising short-term funds.”

Amid the fundraising struggles, HUC-JIR’s spending on institutional advancement (the college’s name for its fundraising department) increased by almost $2 million since 2019, with half of that going to salaries and benefits in the department, audits show. The college’s online directory lists 18 employees working in institutional advancement as of late March – more people than the number of tenured faculty on any individual HUC-JIR campus.

The college has also ballooned its spending on consultants – audits show that spending on “outside services” for management and general operations went from roughly $1 million in 2021 to over $3 million in both fiscal years 2022 and 2023.

Publicly, HUC-JIR has talked little of its fundraising woes, preferring instead to emphasize a decline in funding from Union for Reform Judaism dues, paid by synagogues affiliated with the Reform movement. The URJ gives 44% of dues to the college, an important source of unrestricted funding that made up nearly a quarter of the college’s budget in the 2010s.

Audits show that, since 2015, URJ dues to the college have declined by roughly $4 million – a concerning loss, though far outpaced by HUC-JIR’s fundraising losses.

But the college isn’t on the verge of financial collapse, Mittendorf said. HUC-JIR has a roughly $250 million endowment (mostly donor-restricted funds that won’t balance the budget, but still provide a substantial financial cushion) and is buoyed by investment income as the stock market hits new highs.

At the same time, 2022-23 was a particularly bad period for fundraising that may just be an outlier. But if 2023-level losses are the new normal, and the college can’t stabilize its finances, then HUC-JIR is in serious danger of running out of operating cash sooner, rather than later.

“I don’t think this is an organization that in the next year or two is suddenly going to find itself unable to pay its bills,” Mittendorf said. “But it’s certainly not something that they can sustain.”

In a presentation given to Cincinnati faculty and staff on March 27, the college administration said that HUC-JIR has a “crushing” $6.5 million projected budget deficit for fiscal year 2024, and is aiming for a $3 million deficit in 2025 amid budget cuts, according to a recording obtained by Cincy Jewfolk.

The college is now in the beginning stages of a multi-year fundraising campaign to mark 2025 as the 150-year anniversary since HUC-JIR’s founding in Cincinnati, said Melissa Greenberg, the college’s chief philanthropy officer, in the recording. That includes fundraising in memory of Rabbi David Ellenson, a former president of HUC-JIR, that is being directed toward the college’s Israel programs at his family’s request.

“If we’re able to endow the programs in Israel, that frees up unrestricted dollars that can be sent [to] other places,” Greenberg said in the recording.

“We hope [the upcoming multi-year campaign] will put us in a position to be sustained into the future,” she said. In the process, “we will have created all kinds of what I call philanthropic marketing, which is, how are we talking about ourselves, how we understand our numbers, our needs, and really getting out there in a completely new and different way.”

In the last year, 65%-70% of the college’s fundraising was made up of just seven major gifts, Greenberg said, including a $3 million endowment from a Los Angeles-based former member of the board and two different $1 million gifts.

“We can change the trajectory not in $100 [or] $10,000 gifts, but it is these major gifts that are going to shift us dramatically into the future,” she said.

To Greenberg, fundraising opportunities lie in engaging donors that live outside of New York, Los Angeles and Cincinnati, where most of the college’s funding has historically come from, she told Cincinnati faculty and staff.

“We have been so campus focused, and not leveraging our community of alumni, or people that care about our work, in ways that we will be more in the future,” she said.

Meanwhile, sales of the college’s real estate in New York (assessed at a roughly $14 million market value) and Los Angeles (with an estimated market value of over $4 million) are being finalized, with sales announcements expected by the end of June, according to the recording.

Loss and loathing in Cincinnati

How the college and the Cincinnati campus got here is the 15-year story of an institution buffeted by realities out of its control: Decreased rabbinical school enrollment and increased competition, real questions about the sustainability of a four-campus system, the sudden death of a popular president, the decline of the Reform Movement’s institutions, and unexpected financial difficulties due to the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic.

But it is also a story about the power HUC-JIR has to shape its own future. During the Great Recession, the college avoided closing the Cincinnati campus and instead embarked on a successful all-hands-on-deck fundraising campaign that revitalized the institution – balancing the budget, increasing the endowment, and, for a time, bringing in more rabbinical students.

Then came an administration accused by some Cincinnati stakeholders of deliberately sabotaging the Cincinnati campus and failing its fundraising responsibilities. That same administration proposed the closing of the rabbinical school in a way that students, alumni, and former faculty say was, at best, misleading, and at worst, outright lying to get its way.

For this story, Cincy Jewfolk spoke to nearly 30 alumni, students, former faculty, donors, and HUC-JIR Cincinnati community stakeholders.

The college’s restructuring drove away donors and alumni who had been invested in the Cincinnati campus, many of whom are now too disillusioned, bitter, or tired to want anything more to do with HUC-JIR – at a time when the college perhaps needs their support more than ever. (Most donors reached by Cincy Jewfolk declined to speak on the record.)

President Andrew Rehfeld, who led the college and its restructuring since 2019, recently had his contract renewed through 2029. Rehfeld, at one point, complained to HUC-JIR’s office of recruitment and admissions about there being too many women in an incoming class of rabbinical students, and on a separate occasion, told the admissions team to be more elitist in its recruitment – incidents reported here for the first time by Cincy Jewfolk.

“Andrew has led HUC-JIR with purpose and skill, nurturing and safeguarding the institution in the face of numerous challenges and positioning it for a vibrant future,” said David Edelson, chair of the HUC-JIR Board of Governors in a statement about Rehfeld’s contract renewal.

“We are grateful for Andrew’s persistence and resilience, and we are excited by his vision of HUC-JIR as a laboratory for academic inquiry, spiritual exploration, and cultural creativity, where we study, create, and learn to apply Jewish wisdom.”

The statement made no mention of the college’s fundraising or financial situation.

Now, stakeholders wait and see what the college does next with the Cincinnati campus and the three historic institutions that will remain there after 2026: The Klau Library, host to perhaps the second largest Jewish library collection in the world; the American Jewish Archives, the largest cataloged assembly of American Jewish historical materials and institutional archives in the world; and the Cincinnati Skirball Museum, which has one of the largest Jewish museum collections outside of the coasts.

The Cincinnati campus (Warren LeMay/Wikimedia Commons)

The college maintains it will grow the institutions by combining them into a research center, and is now hiring for an executive director to develop, oversee, and fundraise for the center. Finalists for the job are expected to visit the Cincinnati campus and present their vision for the research center in May.

“I don’t understand how the college-institute is going to be able to support [the Klau, AJA, and Skirball Museum]…if they’re going to be selling off those assets piecemeal, I find that to be a bit of a desecration,” said Rabbi Joe Black, senior rabbi at Temple Emanuel in Denver and a critic of the college’s restructuring.

“They don’t have the money to pay for [establishing a research center],” he said. “The way that it was communicated, ‘We will be able to do this,’ that is something that angers and saddens me. Had [the college administration] been more forthright about the financial situation – but they aren’t.”

What HUC-JIR’s situation means for the rest of the Reform Movement remains to be seen. Many Reform Jews see HUC-JIR’s closure of the Cincinnati rabbinical school as another sign that Reform institutions are abandoning the middle of the country in favor of the coasts. Meanwhile, anecdotally, more rabbis than ever are coming to Reform synagogues from rabbinical schools other than HUC-JIR.

“What’s hard now is, they got what they wanted,” said one former faculty member. But “it’s hard to see anything constructive that’s actually happened.”

In response to over 70 emailed questions for the HUC-JIR administration about the details in this story, President Rehfeld and board chair David Edelson did not deny or refute any aspect of Cincy Jewfolk’s reporting. Here is their full joint statement:

“Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion is cultivating the next generation of Reform Jewish clergy, educators, and nonprofit leaders. These leaders will enter an increasingly dynamic world that requires a strong academic foundation along with the skills and tools to be stewards and sources of strength, wisdom, and compassion for their communities. Across the country, the landscape of higher education, religion, and religious education is shifting, and it is essential that HUC-JIR continues to evolve and thrive as a pillar of Reform Judaism for our next 150 years.

“Business as usual is not a sustainable long-term strategy.

“We intend to maintain the Cincinnati campus as a hub for research, gatherings, and academic pursuits. HUC-JIR leadership discussions regarding the closure of the campus’s rabbinical program dates back to the 1970s. Amidst a long-term enrollment decline and the changing environment for clergy education and Jewish Studies programs, continuing forward as we always have would be irresponsible.

“The process that governed our decisions in Cincinnati included dozens of meetings with faculty, students, alumni, and staff over several years, including over two dozen in 2022 alone. The program changes have been gradual and rooted in the reality that business as usual is not a sustainable path forward. Some elements of this institutional evolution, including academic program and library collection evaluation, are best practices at responsible institutions, but which had not previously been done.

“We recognize and regret that these necessary changes have been painful for members of the HUC-JIR and Cincinnati communities. We sought to minimize impact on current students with a timeline that enables uninterrupted completion of their studies, and we hope that we can maintain our presence in Cincinnati.

“HUC-JIR is preparing the next generation of clergy, from pastoral care, counseling, community leadership, and operations to unparalleled academic rigor and scholarship. As part of this, it’s important that we are a catalyst for a more inclusive community, aspiring toward recruiting and retaining diverse cohorts—in our rabbinical and across all our programs—who are prepared to serve the global Jewish community. While many of the tenets of being a religious leader are founded upon centuries of tradition, their training, and HUC-JIR, must look different in the future than yesterday or today.”

The Union for Reform Judaism, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, and several individual HUC-JIR board members did not respond to emailed requests for comment from Cincy Jewfolk.

Strife and success in the Great Recession

In mid-April 2009, Rabbi David Ellenson, then-president of HUC-JIR, penned a letter to the college community. He had bad news: The college might have to close one, possibly two, of its U.S. campuses.

“HUC-JIR [is] in the most challenging financial position it has faced in its history – even more so than during the Depression,” Ellenson wrote. “I wish with all my heart and soul that this were not so. Yet, all the wishing in the world cannot alter the reality we face.”

Photo of Professor David Ellenson in his office at Brandeis University, 2016 (Wikimedia Commons)

There were two serious financial issues facing the college in the midst of the Great Recession. Firstly, the market collapse meant lower returns from the endowment and other investments to support the college. And secondly, Reform synagogues were reducing or canceling their dues to the Union for Reform Judaism, part of which was earmarked to HUC-JIR and made up a quarter to nearly a third of the college’s total revenue.

Altogether, the college was expecting to lose $7 million-$8 million annually for the next five years – so something had to give. In New York, Los Angeles, and Cincinnati, regional communities rallied to protect their corner of the college, worried about cuts, and warned of “very strong protest and pushback” if their campus was shut down. The New York faculty even drafted a plan that suggested closing all three stateside campuses and consolidating to one New York-based campus.

But there was a feeling that, most likely, Cincinnati would be first on the chopping block – a reflection of debates in the college community about cutting the campus here that had ebbed and flowed since the 1970s.

“The fear [in Cincinnati] was that this was a Los Angeles, New York [board members’] takeover of the college, and Cincinnati was expendable,” said Rabbi Ken Ehrlich, then the dean of HUC-JIR’s Cincinnati campus. “Closing a campus or closing a program is the first thing that you think of when you have a financial crisis.”

But as the college went through a strategic planning process and considered a wide variety of options to stay afloat, a campus closure became more and more unlikely.

“The problem is that nobody really wanted to close a campus,” said Rabbi Irwin Zeplowitz, senior rabbi at The Community Synagogue in New York and, at the time, a member of the HUC-JIR Board of Governors. Zeplowitz recalled being lobbied by passionate supporters of each campus, leading to “a deeply divided board.”

Despite telling the college community about the possibility of closing a campus, Ellenson was adamantly against doing so, according to Ehrlich, and pushed for the board to find another solution to HUC-JIR’s financial issues.

Contacted by Cincy Jewfolk shortly before his death, Ellenson declined to comment for this story.

Meanwhile, it became clear that closing a campus would likely hurt, rather than help, HUC-JIR’s financial situation. “We all came to understand that closing a program or a campus would cut some expenses, but also would result in irreplaceable loss of income,” Ehrlich said.

“Donors throughout the country – including donors on the East and West Coasts – were contributing a great deal of money to the programs housed on the Cincinnati campus,” he said. “It would have been foolish to cut or close those programs and lose that donor support. Fortunately, cooler and wiser business heads took over that prevented any kind of draconian knee-jerk reaction.”

By early May 2009, the HUC-JIR board changed tack and voted against closing a campus, committing to keep all three of its stateside locations. For some board members, doing so was a bet on the college’s future.

“At that point, I spoke up and said, as much as it makes sense logically [to cut a campus], sometimes in Jewish life we do things that are not financially sustainable, but they’re hopeful for the future,” Zeplowitz said. “Clearly, people have spoken, saying, ‘We want to sustain our institution.’”

So the college embarked on a five-year “New Way Forward” plan that raised tuition; cut salaries (including for Ellenson and the rest of the administration); offered buyouts; delayed the hiring of new faculty; sold some of the college’s real estate; and perhaps most importantly, launched an all-hands-on-deck fundraising effort.

“Ellenson made it clear that if we’re going to keep [all the campuses] not only open, but growing, he’s going to have to devote a lot of his time to raising funds,” Ehrlich said. “He also made it clear that he couldn’t do it alone – that all the deans and the directors would have to engage in fundraising to keep their own programs going.”

The fundraising was a quick success, something Ehrlich attributes to Ellenson’s skills, the motivation of HUC-JIR’s dire finances, and recovery in the financial markets. By the end of fiscal year 2009, HUC-JIR raised roughly $17.5 million and had another $9.8 million in future pledges.

Over the next few years, the college received major gifts across its campuses and programs from the likes of the Jim Joseph Foundation, Marcie and Howard Zelikow, the Mandel Foundation, Bonnie and Daniel Tisch, and Taube Philanthropies.

In 2014, HUC-JIR celebrated a successful end to its five-year fundraising campaign, “Assuring Your Jewish Future,” which exceeded expectations by raising $131.3 million – of a $125 million goal – from over 9,000 donors. The budget was balanced, the endowment was growing, and the college seemed to be reinvigorated.

In Cincinnati, fortuitous timing led HUC-JIR to forge a deeper partnership with the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati that helped revitalize the campus here. In 2009, the foundation gave $6.5 million to the $12.1 million renovation of the Klau Library – and in 2010, it sold the Jewish Hospital of Cincinnati for $180 million, infusing the foundation with an influx of cash and a new sense of purpose.

There was “a lot of anticipation about what we were going to do,” said Brian Jaffee, the CEO of the foundation. “A lot of organizations just wanted us to give them a big chunk of money to take some headaches off of their plate, HUC included…and that’s not the way we wanted to operate.”

Editor’s note: Cincy Jewfolk is supported by the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati through its Reflect Cincy grant initiative.

The foundation was being cautious about its next move, wanting to be a collaborative partner rather than just a grant giver. Investing in HUC-JIR seemed like a good way to feed two birds with one scone: Setting the tone for how the foundation wanted to operate while sustaining an important legacy institution in Cincinnati.

In 2012, the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati announced a five-year, $5.2 million investment in HUC-JIR that would support a Cincinnati-based office of recruitment and community engagement to increase enrollment and outreach, and create the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati Service Learning Fellowship Program, which offered scholarships and stipends to Cincinnati rabbinical students to work at local Jewish institutions. The investment made the foundation one of the college’s top donors.

The funding also served to try and rebuild trust in HUC-JIR after the intense conversations about closing a campus.

“We absolutely wanted to strengthen the relationship between the Cincinnati Jewish community and HUC-JIR, and we wanted to make the Cincinnati campus a more indispensable part of the HUC system,” Jaffee said. “We did have high hopes that that would fundamentally change the dynamic.”

Another victory for the Cincinnati campus was a 2015 investment by Joan Pines, a member of the board of governors and also a top donor to HUC-JIR. A major gift (the amount was not publicized) led to the naming of The Joan and Phillip Pines School of Graduate Studies, with a commitment to fund annual fellowships for students and build up an endowment for the school over several years.

With these and other investments, the Cincinnati campus, which had been “kind of mothballed,” Jaffee said, had a new lease on life. Empty buildings were full again, more of the broader Cincinnati community was coming to campus for programming, and the Klau Library, Skirball Museum, and American Jewish Archives were growing their collections. More students were enrolling at the rabbinical and graduate schools, while the faculty started to grow again.

Excluding the library and the archives, by the mid-2010s the Cincinnati campus only required around $4.5 million a year – about 12%-15% – of HUC-JIR’s unrestricted budget to operate, according to former dean Rabbi Jonathan Cohen.

“All at once there was a vibrant campus again, where it had not really felt like that before 2010-11,” Jaffee said. “It really looked like [all the investments were] starting to work.”

But as the college saw success, its structural challenges festered. While the dues payments from the Union for Reform Judaism continued to support HUC-JIR, they were falling year by year as the URJ saw its own financial struggles. The college would have to address the shortfall of an unrestricted income source that, by 2016, still made up 15% of its total revenue and nearly a quarter of its unrestricted budget.

The solution? More fundraising. But the college’s massive fundraising was also a double-edged sword: Much of its new funding was donor-restricted to specific programs, so it couldn’t be used to cover general operations.

“That was always a concern…you raise restricted funds that will pay for the programs, but you don’t have enough unrestricted funds to keep the campus open,” said Ehrlich, who in 2011 became counselor to the president and spent four years working on strategic planning at the college. “A program cannot run if there’s no campus and there’s no college to sponsor it.”

HUC-JIR addressed that by asking donors to make part of their gift unrestricted, which Ehrlich said many donors were happy to do. But that still didn’t fix HUC-JIR’s structural imbalance with a large mostly-restricted endowment, and meant that the college could still struggle to cover its expenses.

Between 2014 and 2020, public audits show that HUC-JIR had annual operating shortfalls of $2-3 million because unrestricted revenue didn’t fully cover operating expenses, even as total revenue and fundraising metrics hit new highs and the college had a positive cash flow.

At the same time, HUC-JIR enrollment was dropping while non-denominational rabbinical schools, like Hebrew College, grew. In 2008, HUC-JIR had nearly 200 total enrolled rabbinical students across stateside programs and students spending their first year in Israel. By 2015, the college had under 150 students.

Low enrollment could call into question fundamental aspects of the college – and resurrect the Great Recession-era debate about having three stateside campuses.

“It’s hard to justify three campuses when you have a total enrollment in the rabbinical school that, 30 years ago, could be found just in Cincinnati,” Ehrlich said. “We all knew that if we don’t have enough students, we can’t sustain the operation. People will correctly wonder: Why do you have as many faculty as you do students? Why do you have a library and an archives that size if you don’t have the students to use them?”

Still, it seemed like the college and the Cincinnati campus, especially after surviving the Great Recession, would come out on top.

“People [in Cincinnati] felt they were stable, that if they had weathered that really direct attack successfully, that [others] would begin to recognize that we had something good going on,” said Rabbi Julie Schwartz, a former administrator and faculty member at the Cincinnati campus.

A new president, Rabbi Aaron Panken – widely popular and considered an excellent fundraiser – came on in 2014. Some Cincinnati stakeholders were unsure of Panken, who had been HUC-JIR’s vice president for strategic initiatives during the Great Recession and, in that role, had been responsible for sharing campus closure plans.

“He said, ‘Please stop looking at me that way, I’m not going to close the campus,’” said Schwartz. Panken “was building things up here, he was in favor of growing…and no one had the sense that he was going to pull the rug out from under us.”

Under Panken’s tenure, total enrollment started going back up, and from 2014-2016, Cincinnati was the preferred destination for rabbinical students out of the three stateside campuses.

But in 2018, Panken suddenly died in a plane crash, throwing HUC-JIR into mourning and a sense of uncertainty about the future. Ellenson came back as interim president to run the college while the board searched for Panken’s replacement – eventually settling on Dr. Andrew Rehfeld. Rehfeld, the first non-rabbi to be president of the college, is a political science professor who spent seven years as the president and CEO of the Jewish Federation of St. Louis.

Many in the HUC-JIR community were excited about Rehfeld’s presidency and what an external non-rabbinic hire could bring to the college. When he was inaugurated in 2019 in Cincinnati, it was also a way to showcase the campus here.

President Andrew Rehfeld speaks at his inauguration in Cincinnati, 2019 (screenshot)

“We looked good,” Schwartz said. “[Rehfeld] took a tour of the campus, it was very positive. So we were still on this high from having so many students and having wonderful programs.

“We had somehow weathered [Panken’s] death, though, not well – but you don’t know you’ve done it wrong until you have proof…and then things changed very quickly,” she said. “So there was a great period of time, the good old days, I think they call them. I think that increases the pain [of what came next].”

The crazy-making of ‘One HUC’

As good as President Rehfeld’s first impressions had been, relations quickly soured with the Cincinnati campus. The new president championed a slogan, “One HUC,” that represented a business-style streamlining, consolidation, and centralization at an institution that had, for much of its existence, been an eclectic and entrepreneurial network of semi-independent campuses.

“We’re not one school, it was never one school,” said Schwartz. “It was three different kinds of schools that put out Reform rabbis who work together.”

Under “One HUC,” Rehfeld and HUC-JIR Provost Rabbi Andrea Weiss proposed a unified faculty structure and curriculum – something many of the faculty, across all three stateside campuses, pushed back against.

But “One HUC” also came to symbolize, for the Cincinnati campus, that it was expendable for the first time since the Great Recession. Word spread that the new administration said Cincinnati wasn’t attractive to prospective students.

“The ‘One HUC’ thing became this umbrella for like, there’s one part of HUC that’s kind of a drain,” said a student on the Cincinnati campus, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation.

“This narrative about the lesser-ness of Cincinnati started to come out…[that] people don’t want to live in Cincinnati because it’s not as progressive as L.A. or New York,” they said. “There were all sorts of weird presumptions about Cincinnati bandied around…I don’t know why they think we’re out here in bumpkin-ville.”

The emphasis on “One HUC” grew as the college started a new round of strategic planning in 2020 amid the sudden pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the course of late 2020 and early 2021, a series of internal and external communications signaled that HUC-JIR was on the cusp of big changes – led by an administration that, to many in Cincinnati, was increasingly untrustworthy.

In October 2020, Rehfeld shocked the college’s office of recruitment and admissions by allegedly telling the staff to be more elitist in their recruitment efforts.

Rehfeld said “that we needed to stop wasting time on low-caliber schools that probably didn’t have people we would want…that, from a statistical perspective, there were less likely to be people talented enough for HUC at such colleges and universities,” said Rabbi Ari Jun, who worked in the office of recruitment from 2019-22. Jun is a graduate of the Cincinnati rabbinical school, a current student at the Pines School of Graduate Studies, and the son of Rabbi Julie Schwartz.

The instructions were baffling. Plenty of successful HUC-JIR rabbis had come from regional and non-Ivy League universities, and it sounded like Rehfeld was insulting them. Rehfeld’s view was also echoed in an internal strategic planning presentation about the college’s mission statement.

Rehfeld “explicitly told us…just focus on elite schools, and [don’t] worry about the others,” Jun said. “Which obviously does not represent the values that I think any of us doing the real work, who are alumni of HUC’s programs, would think that HUC should support.”

Next came a Rehfeld-penned series of letters to the board of governors in December 2020, timed to the days of Hannukah. Rehfeld wrote that the college would “require significant change” while riffing on the story of the Maccabees to discuss the current state of the college.

In his fifth letter of the series, Rehfeld wrote about how the Jim Joseph Foundation – a major funder of Jewish education initiatives and a previous donor to HUC-JIR – opened his eyes to the way the college was allegedly chasing away donors.

“A bit over a year ago, [the JJF] declined to support us with a grant that the team had been expecting, in part because they believe we are using our resources to maintain duplicative programs at unnecessary cost,” Rehfeld wrote.

“That concern has been raised with me frequently by potential donors,” he said. “We will need to inspire greater philanthropy by…demonstrating that the strategic choices we make – whatever they are – increase our mission impact in a financially responsible way that resonates with donors.”

This narrative – that the college couldn’t find funding as a three-campus stateside system – was a marked departure from HUC-JIR’s reality in the 2010s, when the institution’s infrastructure seemed no barrier to record fundraising.

The Jim Joseph Foundation did not respond to a request for comment from Cincy Jewfolk.

Something Rehfeld didn’t mention during his Hannukah letters is that HUC-JIR was in the process of losing one of its most prolific donors: The Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati.

As quickly as enrollment at the Cincinnati rabbinical school increased from 2014-17, prompting the foundation to renew its funding, the number of new students dropped off again. According to the college’s campus preference surveys, in 2019, Cincinnati was the preferred campus for just two rabbinical students in a class of 21 – one of the smallest ever at HUC-JIR.

So the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati decided to move on, having already allocated $9 million since 2012 for the rabbinical school and the office of recruitment – part of a total $18 million given to HUC-JIR since the early 2000s, including investments in the Klau Library and American Jewish Archives.

The decision not to renew funding came from “a creeping dissatisfaction about what was beginning to not work as a result of our pretty significant investment,” said Brian Jaffee, CEO of the foundation. “A sense that it wasn’t going to get much better, and a real fatigue for our staff and trustees that had just had a lot of conversations with HUC over the decade.”

Asked if the decision was a vote of no confidence in how HUC-JIR operated, Jaffee said it was about not having confidence that the overall situation would change.

“Whether that’s because HUC wasn’t able to change it or whether external circumstances were making it difficult-to-impossible for the situation to change, that will be debated for the rest of time,” Jaffee said.

“It was not responsible for us to keep pouring not only millions of dollars, but time and energy in the human resources of this foundation into one sector of what we do,” he said. “We gave [HUC-JIR] the office, we did our part, and there’s just a big community that we needed to really turn our attention to and focus on more.”

With the exception of some small grants to the Cincinnati Skirball Museum, the Jewish Foundation of Cincinnati no longer gives any money to HUC-JIR.

Meanwhile, non-elite recruiting wasn’t the only thing about enrollment that bothered Rehfeld. In early 2021, he came back to the office of recruitment and admissions to allegedly take issue with the gender breakdown of the incoming class of rabbinical students.

Rehfeld “was agitated that we had so many women students in the incoming rabbinical class, and so few men in it,” said Jun. When the recruitment team pushed back on Rehfeld, “his response was that, well, it’s important that we have diverse representation within the class. So if there aren’t enough men in there, it’s not representative.”

The exchange was bizarre to Jun and the rest of the team, especially given HUC-JIR’s longtime reputation as a boys club, as well as its legacy of ordaining the first female rabbi in North America just 50 years ago. Later in 2021, HUC-JIR published an independent investigation into the sexism and sexual harassment long found at the college.

“We had decades and decades of only men training to become rabbis,” Jun said. “It feels tone-deaf for us to be disturbed that there are too many women in the program.”

Jun is a meticulous note taker, and he reported Rehfeld’s comments to HUC-JIR’s human resources department.

HUC-JIR had no direct response to questions from Cincy Jewfolk about whether it stood by Rehfeld interactions with the recruitment team, or how members of the college community and non-male identifying alumni should understand Rehfeld’s comments. The administration did not deny that the interactions had taken place, nor did it refute Cincy Jewfolk’s characterization of those interactions. The college’s statement to Cincy Jewfolk noted that “it’s important that we are a catalyst for a more inclusive community, aspiring toward recruiting and retaining diverse cohorts—in our rabbinical and across all our programs—who are prepared to serve the global Jewish community.”

As the college’s strategic planning plodded on, a spring 2021 update offered bad news about the college’s finances: The Union for Reform Judaism dues were projected to give HUC-JIR just $5.5 million annually over the next few years, a decline of $4 million since 2015. Also mentioned was a pre-pandemic $1.5 million annual “structural deficit” that the college was now trying to address.

But the administration didn’t say that, at the same time, its fundraising had slipped. Audits show that HUC-JIR didn’t experience much of a fundraising bump even as the pandemic saw record philanthropic giving, including to Jewish organizations. HUC-JIR’s contribution revenue (measuring donations and pledges for future giving), which averaged $22.5 million annually from 2015-19, declined nearly $10 million by the end of fiscal year 2021 – a bigger hole than the reduction of URJ dues.

The update also announced the formation of four task forces to evaluate the college’s real estate, Israel programming, libraries, and “the configuration of our North American Rabbinical School.” People in Cincinnati took the hint, and confronted the administration during strategic planning community meetings.

Rehfeld “said changes need to be made, but he didn’t elucidate what kind of changes…he kept saying that closing the rabbinical school was an option, but no decision had been made yet,” said the anonymous Cincinnati student. “You couldn’t get him to say directly what his plans were for the Cincinnati campus.”

As time went on, former faculty and alumni said that “One HUC” became a way to stifle voices pushing back on the strategic planning process, to the point that some staff were afraid for their jobs and rabbinical students worried about retaliation in their post-graduation placement process.

“Every time [Rehfeld] said, ‘we are One HUC,’ [it meant] we’re all on the same page, we all agree – there was no expectation that you would ever dissent,” said Schwartz. “People felt threatened, absolutely…’If you don’t agree with us, you need to leave.’ I think that means we’ll get rid of you, don’t disagree with us.”

The college’s strategic planning task forces were mostly a sham, designed to affirm the administration’s agenda without question, say people with knowledge of the process. The administration made a habit of bypassing or altogether ignoring the task forces.

One example was the administration’s attempt to quietly offload the Cincinnati Klau Library to both the University of Cincinnati and the University of Chicago (Rehfeld’s alma mater), which members of the libraries task force only discovered – by accident – after months of meetings.

The University of Cincinnati and the University of Chicago did not respond to requests for comment.

The Klau is HUC-JIR’s primary research library, known for its substantial collections on the traditions, history, and philosophy of world Jewry across more than a dozen languages – including Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese – and a renowned assembly of Jewish liturgical music. In 2021, its budget was cut by 22%, severely reducing acquisitions, which the libraries task force warned would make the Klau unable to stay up-to-date for research.

By the end of the year, news of the attempted offloading reached students and the broader Cincinnati community. The libraries task force did not recommend offloading the Klau – and the task force evaluating the rabbinical schools never finished its work or gave any recommendations.

By October 2021, the dominoes were falling faster as the college published an essay, written by Provost Rabbi Andrew Weiss, revitalizing the decade-old debate about closing a campus. In the essay, Weiss reintroduced questions about the college’s stateside three-campus system that “internal and external pressure prevented HUC-JIR from asking when faced with the [Great Recession].”

Worry spread, and people more aggressively questioned what the plan was for the Cincinnati campus.

“Students, faculty, myself included…asked on more occasions than I could count, of members of the national administration, if there was any intention of closing the Cincinnati campus,” Jun said. “The response we were given, time and time again, was ‘no.’

“And I can’t understand that answer, combined with the circumstances that existed, as anything other than willfully misleading folks who are stakeholders in the process,” he said. “Because everybody who [asked the administration] meant ‘closing the Cincinnati campus’ as ‘shutting down its programs.’”

While the administration continued to deny that closing Cincinnati was on the table, many on campus felt dazed and gaslit.

“It was crazy-making…because it didn’t make any sense,” said Schwartz. “People were like, back and forth, ‘Is this really happening? No, it couldn’t be happening, we must have misunderstood’ — until it was very clear that we weren’t misunderstanding.”

Said the anonymous student: “I don’t know how all of a sudden it went from ‘One HUC’ to ‘we’re gonna shutter this rabbinical school,’ because it was all behind closed doors.”

‘A playbook for everything to do wrong’

Rabbi R., an alum of the Cincinnati rabbinical school, considers themselves a has-been coastal elite. When starting at HUC-JIR, they had zero interest in coming to Cincinnati.

But after a change in life circumstances, Rabbi R. changed tack, moved here for rabbinical school – and learned to love the Queen City, especially as a place for raising a young family. The rabbi asked to stay anonymous for fear of retaliation from HUC-JIR.

“There has been such a history of HUC being its own community here, between staff and faculty and professors raising kids and families together,” they said. “I felt like HUC was a place that was for my family, and not just for me.”

With tour groups visiting on Saturday mornings, the Scheuer Chapel was “the place to be in Cincinnati.” Another plus: While Rabbi R. had peers in New York working multiple jobs to scrape by with the high cost of living, Cincinnati was remarkably affordable.

The rabbi remembers hosting a welcome party for some students from other campuses before the pandemic. One, from New York, was astonished at how they lived.

“She just could not believe that we were renting a house for less than what a person’s bedroom in a shared apartment would cost in New York and L.A.,” Rabbi R. said. “A whole house with a backyard in suburbia, driving our cars. And we could afford it without taking out very many student loans.”

That’s why Rabbi R. was surprised when the HUC-JIR administration released two white papers in early 2022 officially recommending that the college shut down its Cincinnati rabbinical school.

Provost Rabbi Andrea Weiss’ analysis of the different stateside campuses (framed as, “Which locations are best for rabbinical formation?”) fed Cincinnati suspicions that the HUC-JIR administration was biased against them.

Weiss noted that while New York City and Los Angeles are the first and second largest Jewish communities in the U.S., Cincinnati is in 41st place, with far fewer Reform congregations in its immediate area. Meanwhile, Ohio’s Republican-majority government, largely anti-LGBTQ and focused on culture war issues like denying reproductive rights, allegedly made students prefer the more welcoming liberal atmospheres of California and New York.

“This suggests that our efforts to attract a diverse student body might be more difficult in Cincinnati than in Los Angeles or New York,” Weiss wrote.

That didn’t ring true for Rabbi R. and other students in Cincinnati.

“I had classmates who, when the administration was saying, ‘Well, nobody wants to come to Cincinnati’…my friend raised her hand and said, ‘I was assigned to come to this campus. And now there is no place I would rather be,’” they said. (Before 2020, the college assigned students to campuses while considering their preferences.)

“There’s a discrepancy between what people imagine that Cincinnati is, or the Midwest, and then actually being here is so different, and such a breath of fresh air, honestly, for those of us who come from the East Coast and love it.”

Weiss reported that the one clear benefit of Cincinnati was affordability. HUC-JIR’s 2021-22 cost of attendance estimates showed that going to rabbinical school in Cincinnati was roughly $6,500 cheaper than in New York and L.A. (For the 2023-24 school year, HUC-JIR estimates that Cincinnati is now $7,600-$8,000 cheaper than the other campuses.)

But Weiss brushed off the “relatively small gap” in cost as something the restructuring could solve.

“Of all the factors that distinguish the campus cities, cost of living is one of the few differentiators that the College-Institute could offset through increased scholarships and stipends,” Weiss wrote. “Something we believe philanthropists would be more eager to support if we made structural changes.”

The restructuring proposal, and HUC-JIR’s confidence it could address affordability, made little sense to Rabbi R.

“It speaks to some elitism that feels prominent when you eliminate the only affordable campus,” they said. “You’re asking people to take out a quarter of a million dollars in loans [to go to rabbinical school]. If someone comes in and doesn’t have anything to their name to pay for this – which I mean, how many 22, 23-year-olds do? They probably just have more debt from undergrad…it doesn’t help the admissions case to me.”

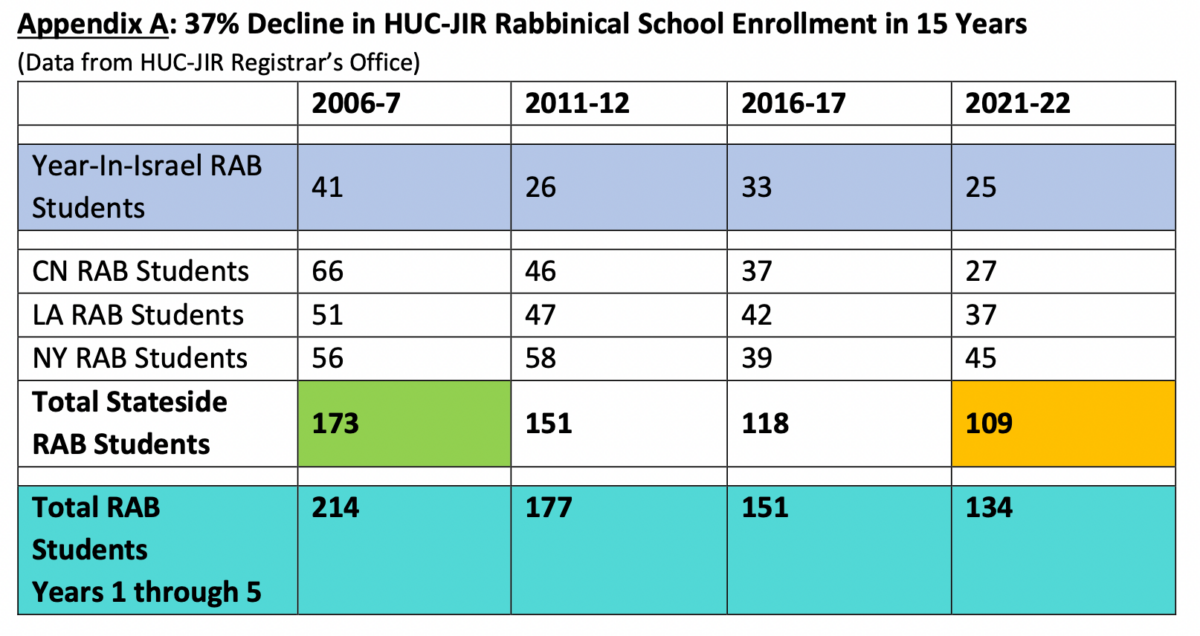

Admissions were an increasingly sore point between Cincinnati and the college administration when it came to the restructuring proposal. According to the white papers, HUC-JIR’s total stateside enrollment had declined by 37% since 2006, with the Cincinnati campus seeing the biggest drop relative to other campuses – from 66 students in 2006 to 27 students in 2021, a 60% decline. In 2021, the New York campus had 45 students, and the L.A. campus, 37.

Chart from “A Recommendation for Restructuring HUC-JIR’s Rabbinical School” that shows slices of enrollment data (screenshot)

The numbers positioned Cincinnati as the obvious underperformer. But many Cincinnati stakeholders and alumni thought HUC-JIR had sabotaged its own enrollment by moving away from in-person recruitment, and by not having a full-time Cincinnati-based recruitment staff since 2018.

“I know that every rabbinic school in the country is dealing with issues, I get that enrollment is down,” said Rabbi Joe Black, the senior rabbi at Temple Emanuel in Denver, who interned in the admissions office as a Cincinnati rabbinical student in the 1980s.

“I also understand that the way that recruitment was done in the past, with a lot of personal one-on-one attention from the national office of admissions, I have not seen that,” he said. “My question is, to what extent was the office of admissions decimated? It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

From 2013-2018, the HUC-JIR office for recruitment and admissions was led by Rabbi Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi, a longtime adjunct professor at the college, who at that point lived in Cincinnati.

Staff didn’t exclusively recruit for one campus’ rabbinical school, but “having somebody who has firsthand knowledge of the campus and a relationship within the region tends to yield better recruitment results for a particular campus,” said Rabbi Ari Jun. “What that meant is, because [Sabath Beith-Halachmi] was a Cincinnatian, somebody was covering Cincinnati.”

But once she left, there was no Cincinnati-based recruitment person until early 2019. That’s when Jun was brought on in a quarter-time position to help recruit for the rabbinical schools and as the sole recruitment person for the Cincinnati graduate school.

Sabath Beit-Halachmi did not respond to interview requests from Cincy Jewfolk.

In 2020, Jun was upgraded to a half-time position – which is where he stayed for the next two years while the college told him there was no money for a full-time Cincinnati-based recruitment staff.

That made Cincinnati the only stateside campus without a full-time staff member doing recruitment (there was a full-time Cincinnati staff member assisting the office, but not working directly on recruitment, Jun said).

The college was also moving away from in-person recruitment, in part because of the social distancing brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. On a Shalom Hartman Institute podcast episode titled “The Great American Rabbi Shortage,” Rehfeld said in-person recruitment was a challenge because of the contractions of Reform institutions like the Union for Reform Judaism and the Reform youth movement, NFTY.

“So long as there were regions of the URJ, for example, there used to be regional offices,” Rehfeld said. “It was much easier to plug into the regional programs and the regional conventions…and when that shifted, we were continuing to do our work, but without that kind of natural gathering [place].”

To replace in-person recruiting, the college spent more than a quarter of a million dollars on online advertising and a digital targeting and recruitment system, “which was something that produced close to zero yield,” Jun said.

Rehfeld “felt that we could be doing recruitment work much more intelligently if we would just follow certain data-related ways of doing our jobs, like getting better leads through who’s taking the [Graduate Record Examinations] and things like that,” he said. “I don’t know if in premise, it [should never] have been attempted, but it did not produce results.”

The HUC-JIR administration did not answer questions from Cincy Jewfolk about its admissions strategy.

But the decade-long decline in enrollment at HUC-JIR is hard to ascribe to any particular change, Jun cautioned, and year-to-year numbers could vary somewhat wildly.

Across the field of rabbinic education, non-denominational rabbinical schools grew as American Jews became increasingly unaffiliated with movements. HUC-JIR’s Conservative Jewish counterparts, the Jewish Theological Seminary and the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies, also saw their enrollment drop. The HUC-JIR white papers saw this as a sign that, in today’s day and age, Jews are simply less interested in becoming rabbis.

Over the years, a variety of Cincinnati campus-based shabbatons and in-person engagement programs for high school and college students had also been shut down, which likely affected the pipeline of prospective students. In his podcast interview, Rehfeld said the college needed to get back into those kinds of programs.

What did become clear, according to HUC-JIR campus preference data, is that after 2019 – when only two students listed Cincinnati as their first choice of campus – slowly but surely interest in Cincinnati trended back up. In 2021, seven students listed Cincinnati as their first choice of campus, equal to the number of students who preferred New York that same year.

Perhaps tastes were changing – or once again having a Cincinnati-based recruitment staff, even if part-time, was working.

“The pipeline between when you start working on recruitment with the average individual, and when they apply, and when they matriculate – it’s not so short,” Jun said. “So if you cut out basically a year, year and a half of recruitment work in a particular region, you don’t just see that in the specific year in which it occurred, but…for a few years.”

Still, the HUC-JIR administration stuck to the basic fact that there were fewer students in Cincinnati and, according to the administration, better reasons to keep residential rabbinical schools on the coasts than in the Midwest.

But out of all the details of the restructuring proposal, Cincinnati stakeholders and alumni were perhaps most bewildered by the financial picture the HUC-JIR administration painted.

As the college faced a projected $8.8 million budget deficit in fiscal year 2022, a severe reduction in Union for Reform Judaism dues, and a decline in fundraising, the administration estimated that cutting the Cincinnati rabbinical school would save just $750,000 to $1 million a year by 2026.

To the administration, those were “significant projected annual savings,” that tracked “rabbinical school administrative staff savings, not additional savings from adjustments to facilities and other support services.”

At the time, the college did not share how the figures were calculated or how those savings would help balance the budget. HUC-JIR also did not answer questions from Cincy Jewfolk about the savings estimate.

“I don’t know what problem the closing of Cincinnati is the solution to, because it doesn’t appear to me to be a financial solution,” said Rabbi David Locketz, senior rabbi at Bet Shalom Congregation in Minnesota and a graduate of the Cincinnati rabbinical school.

Alumni pointed out that cutting the rabbinical school would still leave HUC-JIR on the hook for owning and maintaining the land and buildings of the Cincinnati campus, including for the Klau Library, American Jewish Archives, and Skirball Museum. At the same time, many longtime supporters of the college would be alienated and stop giving, costing HUC-JIR yet more money.

The college administration offered vague ideas about turning the Klau, AJA, and Skirball into a research center, but did not have specific plans for what came next for the campus or blueprints for developing the research center. As a result, many Cincinnati stakeholders became convinced that, against all reason, the HUC-JIR administration simply wanted to shut down the Cincinnati campus.

“To me, that was the number one argument being made, that was reasonable, about…something nefarious going on here,” said Locketz, who otherwise does not think that the administration maliciously targeted Cincinnati.

“There were a lot of voices who I respect, who were [telling the administration], ‘Fine, if you have this great plan for Cincinnati, show us, tell us what’s going to happen there. And the fact that you can’t, or you haven’t even had those conversations, points to the fact that nothing is going to happen there,’” he said.

Students on the Cincinnati campus, collaborating on questions and taking group notes to press the administration, had several tense meetings with President Rehfeld and Provost Weiss. Both were visibly defensive in the face of repeated questions about how closing the rabbinical school and establishing a research center would affect the college’s deficit.

“He just kept saying, ‘We don’t have all the answers yet,’ or, ‘We don’t know what it looks like yet,’” said the anonymous Cincinnati student. “It was just this performance, so they could say that they had met with students, but there were literally no answers.”

Said one former faculty member: Students “felt like the administration was basically lying to them…it seemed like every meeting they had with [Rehfeld], he would say something that would end up just horribly offending them.”

In the weeks leading up to the April 11 board vote on the restructuring, the debate was contentious, playing out across Jewish and non-Jewish press, email chains, the personal blogs of rabbis, and social media – including an anonymous Twitter account harshly criticizing the administration and attacking Rehfeld.

A letter from the Ohio Attorney General’s office even warned that the college may be investigated for not meeting donor obligations. In response to questions from Cincy Jewfolk, an emailed statement from the office of the Ohio Attorney General said it “could not confirm or deny the existence of or potential for an investigation [into HUC-JIR], and charitable investigations are confidential under Ohio Revised Code.”

At the Cincinnati campus Founders’ Day celebration, retiring faculty member Rabbi Mark Washofsky used his speech to publicly attack the restructuring plan, and received a standing ovation from the audience.

“The times, we are told, are a changing…the college can no longer afford a 20th century institutional footprint. Something’s gotta give. And guess what? These buildings you see here, they sit right smack dab in the middle of flyover country,” Washofsky said.

Rabbi Mark Washofsky criticizes HUC-JIR’s restructuring plan, 2022 (screenshot)

“But if the axe was gonna fall, what about that vision [of founder Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise]? That thing about academic excellence? Is that also a 20th-century thing? No, no, not to worry. We can handle that,” he said, satirizing the administration. “Once we’ve relocated and downsized – I mean, right-sized – our operation will simply apply the label ‘academic excellence’ to whatever’s left.”

An alumni letter against the plan racked up nearly 500 signatures, alleging that the plan would be a disaster for the college.

“The current plan does not demonstrate that a serious viability study, nor a study of long-term financial consequences, has been sufficiently undertaken,” it said. “Moreover, the plan lacks any future budgeting, timetable, or business plan associated with ‘reimagining the Cincinnati campus’ and developing a ‘low residency clergy program.’”

Another alumni letter supporting the plan gathered just 130 signatures, and emphasized trust in the HUC-JIR administration.

“In the past few months, we have watched members of the Administration endure unfounded rumors and ad hominem attacks leveled by those who are most critical of the Administration’s strategic planning,” it said. “The vitriol expressed on social media, by email, and in other informal channels…does require our public condemnation.”

On April 11, more than two-thirds of the board of governors voted to enact the restructuring plan, sunsetting the Cincinnati rabbinical program by 2026 and tasking the administration to create a low-residency clergy school no later than 2025 and a research center in Cincinnati – “with recognition that the success of all new projects depends on new financial support.”

A strategic planning update noted that the new programs “will require a full, detailed plan of action, with likely implementation over a period of years. We will move quickly to share additional detail about these initiatives over the coming weeks.” There have been no updates on HUC-JIR’s strategic planning page since April 2022.

As part of the board vote, the 1950 consolidation agreement between Cincinnati’s Hebrew Union College and New York City’s Institute of Jewish Religion – the foundation of the current HUC-JIR – was amended: A legal provision that mandated HUC-JIR “permanently maintain rabbinical schools” in Cincinnati and New York was removed. There is no such provision for Los Angeles.

While no longer a voting member of the board of governors, Rabbi Irwin Zeplowitz still participated in the board’s discussion about the restructuring.

“What’s fascinating is how similar [conversations] were to 15 years ago,” he said. “I don’t think anybody did this without a heavy heart. I think the many people who spoke out in [the plan’s] favor were anguished by it. There were people who were in tears who voted for it…no one, that I recall, felt that this was a good decision. But the majority felt it was the right decision.”

For students, former faculty, and many alumni, it was a bitter and alienating end to the hard-fought effort to save the Cincinnati campus. The administration continued to refute that it was closing the campus, instead saying the campus was being repurposed, retasked, or reimagined. For many, trust was completely broken with HUC-JIR.

“Without a program, why keep the campus?” said Rabbi R. “Honestly, it’s sad, it’s a piece of our history in the Cincinnati Jewish community. But what’s the point, with no program and no people? And what’s the point in continuing to pay professors just to teach virtually from Cincinnati?”

After the vote, the office of recruitment polled first-year rabbinical students in Israel about their preferred campus. The results defied expectations.

“Despite it not being an option provided, the second most number of students requested to go to Cincinnati,” Jun said. “That means they had to specify to us in writing, ‘I know I can’t do this, but I would like to do this.’”

As Jun remembers, just one or two students listed the Los Angeles campus as their first choice.

A campus in free fall

I. Closing the graduate school

Soon after the board vote, the fabric of the Cincinnati campus started to come apart as the Joan and Phillip Pines School of Graduate Studies faced de-facto closing – part of a domino effect of decisions emptying the campus and imperiling HUC-JIR’s future in Cincinnati.

For many years, the Cincinnati campus had basically run two schools for the price of one: Faculty taught both rabbinical and graduate students together, a defining feature of the graduate school. Learning alongside future rabbis was a unique experience for the graduate students, many of whom were not Jewish.

“If you’re not Jewish, thinking about religious topics together with advanced learning clergy who are Jewish, that’s just a transformative kind of experience,” said Michael Graves, a professor of biblical studies at Wheaton College, alum of the graduate school, and co-chair of the school’s alumni association.

Critics of the college’s restructuring – and the administration itself – predicted that cutting the Cincinnati rabbinical school would be detrimental to the graduate school. But, as with other aspects of the restructuring, the administration did not have a specific plan for the graduate school, instead telling stakeholders that it would be evaluated after the April board vote.

“I think the announcement of the closing of the rabbinical school hit graduate alumni hard,” Graves said. “Grieving the loss of an experience that many of us had [also] makes us sad that other people will not have it.”

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency was told that the graduate school would “begin disassociating from Cincinnati’s physical location and allowing students to enroll on its other campuses.”

That didn’t happen. Later in 2022, with no guarantees and no concrete plan, Joan Pines – the prolific donor who supported the graduate school named after her and her late husband – froze her contributions to new student fellowships and to building the school’s endowment.

The 76-year-old graduate program stopped accepting new students. Remaining students have tuition and a stipend paid through their fourth year, then are on their own to finish dissertations.

In October 2023, HUC-JIR formally announced that the graduate school was shuttering, though in conversations with alumni, the administration characterized it as a five-year pause – not a closing – after which the college would re-evaluate its graduate offerings. Graduate programs on the New York and Los Angeles campuses were also cut.

Reached by Cincy Jewfolk, Joan Pines and her family declined to comment for this story.

II. Buyouts

For senior faculty and staff on the Cincinnati campus, HUC-JIR’s glowing talk that restructuring would create “a robust academic life for our faculty and students” culminated in late 2022, when the administration offered buyout packages.

While all of the six tenured faculty rejected the buyouts, preferring to leave on their own terms, non-tenured faculty and staff knew they had little choice but to accept. Ultimately, they would have no place on a campus without full-time students, and had none of the job security that tenure afforded.

“If you’re not taking in new students, then I’ve got nobody to teach the foundational courses to…I surely don’t need to teach electives,” said Rabbi Julie Schwartz. Schwartz was a non-tenure joint faculty-administrator who, in the early 1990s, founded one of the first rabbinic clinical pastoral education (CPE) programs in the country on the Cincinnati campus.

Three retirement-age staff at the Klau Library took the buyouts while other staff and faculty planned their exits separately.

“Everyone knew what was happening, so it was an open secret, but the fact that it was happening was like a constant Chinese water torture – who is next?” Schwartz said. “Certainly [the students’] education has been affected by this, because they saw what was going on.”

Schwartz officially retired from HUC-JIR in August 2023, having taken a buyout after the Cincinnati campus’ CPE program was shut down. But soon after, she relaunched the program at the Jewish Hospital – a decision borne both from love for her work, and its necessity.

“I am not old enough to get my [full] government health benefits,” Schwartz said. “So some of us, we were retired, but I can’t retire. I have to keep working.”

Exits continue: Rabbi Jonathan Hecht, dean of the Cincinnati campus, and Cantor Yvon Shore, director of liturgical arts and music, are leaving the college this year. HUC-JIR will now have to figure out how to support its remaining Cincinnati rabbinical and graduate students with a dwindling staff.

III. Sotheby’s in the Klau

At the Cincinnati Klau Library, staff are anticipating layoffs after being informed of budget cuts – expected in July – across the HUC-JIR library system. The Klau, which has usually had a roughly $2 million budget (largely from HUC-JIR’s unrestricted funds), will be reduced to operating on just half a million dollars of endowment funds in fiscal year 2025.

As most of the library staff are concentrated in Cincinnati, the expectation is that at least half of the roughly 12 full-time Klau employees will be laid off.

The Cincinnati Klau Library (Warren LeMay/Wikimedia Commons)

But budget cuts and layoffs aren’t the only way the library is likely to be reduced. In early 2024, Yoram Bitton, HUC-JIR’s national director of libraries, resigned after allegedly being pressured by the administration to sell rare books from the Klau.

President Rehfeld denied that the college planned to do so, in both internal emails (obtained by Cincy Jewfolk) to all of HUC-JIR’s stateside faculty, and in the private Facebook group of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Reform movement’s rabbinical association.

“We have no plans to sell or ‘deaccession’ the [rare books] collection,” Rehfeld said in a statement to faculty and CCAR rabbis. But the college is “formalizing our collections policy and engaging an independent consultant…to understand the value of our holdings.”

If the evaluation finds a holding that is “redundant or not central to our mission, it is possible we would consider deaccessioning it,” he said. Rehfeld noted that selling any rare item would have to be approved by HUC-JIR’s board of governors.

But in mid-March, the “independent consultant” that came to evaluate the Klau holdings was Sharon Liberman Mintz, the international senior specialist in Judaica for the auction house Sotheby’s. Along with Mintz came Shaul Seidler-Feller, another Judaica specialist at Sotheby’s.

Rehfeld’s internal statement did not explain why the college chose not to rely on the expertise of Bitton and existing Klau staff to evaluate the rare books collection and formalize the college’s collections policy, nor did it mention Sotheby’s.

HUC-JIR did not respond directly to Cincy Jewfolk questions about Sotheby’s evaluating the Klau holdings, and the college did not deny that it might sell rare items from the Klau Library. “Some elements of [HUC-JIR’s] institutional evolution, including academic program and library collection evaluation, are best practices at responsible institutions, but which had not previously been done,” the college said in its statement.

Sotheby’s did not give an on-the-record statement to Cincy Jewfolk about its relationship with HUC-JIR. Neither Mintz nor Seidler-Feller replied to requests for comment.

Mintz will give a report to the administration with her evaluation of the Klau holdings, which is expected to include options for potential sales. Internally, the administration is reportedly talking about selling rare books as a necessary financial move to save the college from its crippling deficits.

One of the items potentially being put to auction is the Klau’s set of the Bomberg Talmud – one of 12 known complete 16th-century sets of the earliest press-printed Talmud in history. The Klau’s Bomberg Talmud is the only publicly available set in North America, and the only set held by a Jewish institution. In 2015, Sotheby’s auctioned a Bomberg Talmud set that was bought for $9.3 million by a New York businessman. HUC-JIR’s statement to Cincy Jewfolk did not deny that the Bomberg Talmud may be up for sale.

Deaccessioning materials is not necessarily unusual for libraries and museums – even if it evokes controversy about stewardship and financial issues – and funding from sales is often reinvested into library work and making new acquisitions. Nor is it out of the ordinary to have a specialist from an auction house evaluate a unique collection, given the expertise required, according to research library specialists consulted by Cincy Jewfolk.

A major concern for the scholarly community is that rare items at auction are usually sold to wealthy private buyers, which results in those items no longer being available to scholars and the general public. Private buyers also may not have the facilities or knowledge to preserve old materials, which could affect their longevity.

But among Cincinnati stakeholders – especially given Bitton’s resignation and the college’s financial troubles – there is little trust that HUC-JIR would sell rare items for the sake of the Klau, or that its deaccessioning process would be an ethical one. The college has no formal deaccessioning policy, but its public audits state that “proceeds from the sale of collection items are required to be used to acquire other collection items.”

For alumni, the lack of trust stems from HUC-JIR’s poor communication and transparency about the Cincinnati campus.

During the debate over closing the Cincinnati rabbinical school, alumni “were asking…show us how this is going to solve all the financial problems that you’re saying it’s going to solve, and we never got anything,” said one alum of the Cincinnati rabbinical school, who asked to stay anonymous for fear of retaliation.

Since the closing, news like Cincinnati staff exits haven’t been widely announced by the administration. “No one was informed unless they heard about it through Facebook or other means,” the alum said. “So it just feels like, how much can [the administration] hide from everybody – and the Klau is just another example of that.”

To some, Rehfeld’s plan for the rare books collection is eerily similar to the path HUC-JIR took when closing the Cincinnati rabbinical and graduate schools: deny stakeholder fears, while also starting an evaluation process that opens the door to doing exactly what stakeholders feared.

Rehfeld’s internal statement did not explain how a rare book could be evaluated as redundant or not central to the mission, nor did HUC-JIR’s statement answer Cincy Jewfolk questions about the evaluation process. The expansive mission statement of HUC-JIR’s library system is “to collect, preserve, and provide access to the record of Jewish thought and experience throughout the ages.” Thinking of rare books as redundant is generally questioned by some scholars, who point out that rare items have unique provenances.

The move to potentially sell rare items from the Klau is a marked departure from an institution that once called the library the “soul of the college,” and invested in the Klau even amid the financial struggles of the Great Recession.

“The Klau Library resides at the very heart of our enterprise,” wrote then-President Rabbi David Ellenson in the 2009 president’s report about the library’s $12.1 million renovation. “It offers tangible testimony to the absolute commitment we at HUC-JIR have…to sustaining and advancing academic study, research, publication, and teaching for the benefit of the Jewish people and all humanity.”

The Klau’s rare book room is named after Ellenson, prompting some Cincinnati community members to see HUC-JIR’s current direction as an attack on his legacy.