We were, relatively speaking, late to the iPhone world. My wife and I hung onto our “dumb” phones for a long time, though we are big Apple fans. But finally, about 2 years ago now, we joined the smart phone world, got our iPhones. And with them, Siri.

It was both fun and helpful to be able to ask Siri to do tasks.

“Siri, text my wife.”

“Siri, remind me to put in laundry when I get home.”

“Siri, where’s the closest gas station?”

Oh, and on one scary road trip:

“Siri, directions to the closest hospital.”

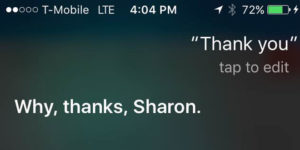

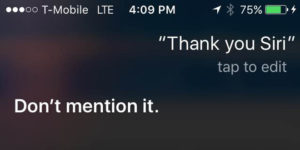

And Siri would do (usually) what I asked, respond and then always I would say, “thank you.”

But I started to feel silly. I don’t thank my oven, or my washing machine. But because I was using verbal language to interact with Siri the thank you came out of my mouth automatically. I became self-conscious about it, so I started fighting the impulse.

And when I’d fight the impulse and not say thank you, it wouldn’t feel silly, but it felt so wrong. No, Siri’s not a person and no she wouldn’t care whether I say thank you or not, but it felt wrong to ME. And that’s when I realized that Siri is like a challah.

It was Susie Chalom who I first remember hearing explain why we cover the challah. Many years ago I remember her telling a group of preschoolers that we cover the challah so it won’t feel sad. At meals throughout the week the bread is the focal point. We say Hamotzi, have a taste of bread and begin our meal. But on Shabbat, there are candles and there is wine, and the Challah is last. We cover the Challah, she told the children, so it won’t feel sad. Then it doesn’t have to watch as the other things come first and when we uncovered it we are ready to give it our focus and say Hamotzi.

The story continues by asking, “Does a Challah really have feelings? Does it really feel sad?” And of course the answer is no, which brings us to conclusion, the moral of the story. No, it doesn’t. But we practice on it anyway. We practice being careful of the feelings of the challah so that being careful of feelings becomes a habit to us. And if we are careful with the feelings of a piece of bread, that doesn’t really have the ability to be sad, how much more careful we will be with the feelings of the people around the table who do.

And that’s why it felt wrong to not say thank you to Siri. My habit was that when asking for something and receiving it, I say thank you. And to fight that impulse just felt wrong. So I went back to saying thank you each and every time to Siri, and decided it didn’t matter if it felt silly because it also felt so right. How awful it would be to lose the habit of expressing gratitude. What if not saying thank you to Siri became not saying thank you to the cashier at the co-op, the person who held the door, my wife when she passed me the salad? Siri is like a challah.

A while back my son got an iPad. For a person with Dylsexia, this can be a very powerful tool, and he uses it in many ways to support his learning as well as for much of his pleasure reading. He especially likes to use Siri to look things up, because it saves him from having to figure out how to spell what he is searching for. “Siri, show me a picture of Jane Goodall.” “Siri, when is The Force Awakens coming out on DVD?” “Siri, when is the first night of Passover?” And I noticed that each time he has these interactions with her, he then says, “Thank you, Siri.” And it makes me smile.

A while back my son got an iPad. For a person with Dylsexia, this can be a very powerful tool, and he uses it in many ways to support his learning as well as for much of his pleasure reading. He especially likes to use Siri to look things up, because it saves him from having to figure out how to spell what he is searching for. “Siri, show me a picture of Jane Goodall.” “Siri, when is The Force Awakens coming out on DVD?” “Siri, when is the first night of Passover?” And I noticed that each time he has these interactions with her, he then says, “Thank you, Siri.” And it makes me smile.