Is “Fiddler on the Roof” a Jewish Text?

I’ve been walking around my kitchen humming If I Were a Rich Man. I just saw “Fiddler on the Roof.” It was staged as an opera, complete with a full symphony, ballet dancers, and singers with rounded voices rather than the sharp-edged belt of Broadway. Sponsored by the Jewish Foundation, it felt like a big family reunion. I sat in the top gallery, surrounded by people who clearly thought it was totally fine to chat and sing along during the performance (a lot like synagogue).

I grew up with Fiddler. It premiered in 1964 and became a massive success, shaping Jewish identity for many American Jews ever since. As kids, I remember my sister and I twirling around the house with brooms, belting Matchmaker, Matchmaker, genuinely believing that’s how we’d find our husbands. (Spoiler alert: we didn’t.)

In high school, where I was the only Jew, I was cast as Yente. Maybe it was my looks, or maybe it was the touch of Yiddish I had picked up at home. Either way, I was typecast. My dad said I looked just like my grandmother in a headscarf. Still not sure if that was a compliment. I didn’t get to play the beautiful lead, but being Yente somehow fit.

Fiddler as Cultural Memory

Fiddler has always been the background music to my Jewish experience. But it’s fiction, a simulacrum—a reproduction of something that never quite existed. Yes, the shtetls of the Pale of Settlement were real: poor, oppressed, plagued by violence. But they were also home to rich, self-sustaining Jewish communities—schools, systems of governance, intellectual and spiritual life. And no, they didn’t break into songs about Yente or Fruma Sarah.

The world Fiddler gives us is a shadow version: less violent, more nostalgic, more palatable. Our families may have fled those places, but Fiddler smooths out the sharp edges. So is it still our story? Do we claim it because it feels familiar, even if it’s not actually true?

Fiction Yes—But Also Truth

This time, watching Fiddler felt like comfort food. It wasn’t emotionally or intellectually challenging. It wasn’t even particularly exciting. But it was deeply familiar. It felt good to hear the songs we know by heart, to be part of a communal sing-along with the rest of the Jewish audience. It felt like solidarity. Like collective imagination.

I must also ask the age-old question: Is it good for the Jews? Does portraying Jews as an insular group with old-world customs reinforce stereotypes at a time when antisemitism is rising? Or is Fiddler exactly what we need right now?

A Whisper of Collective Memory

I keep thinking about my grandmother. She used to sing those songs at the top of her lungs—because they were hits when she was raising kids. This wasn’t her life; she was born in 1920s Germany. Fiddler was fantasy for her, too. But it helped her imagine her relatives’ lives. And it helped me imagine mine.

My grandfather’s family had been in the U.S. since before the turn of the century. Still, Fiddler somehow felt real. It functioned like a collective origin story.

The Author and her podcast partner at Music Hall (courtesy)

A New Kind of Jewish Text

So yes, “Fiddler on the Roof” is a Jewish text. In fact, I think it’s a new kind of Jewish text, not compiled by Rabbis, but still comforting and familiar, like the prayers we recite in synagogue. We know the words by heart. We show up not necessarily for the plot, but for the experience, the shared memory, the imagined origin story of a place none of us are really from. And yet, it still connects us.

Fiddler serves as a kind of communal Haggadah—a retelling of an exodus with stories of hardship and hope that we revisit year after year. It invites us to sing along, to place ourselves in the characters’ shoes, to create midrash about Tevye, Golde, Yente, even Fruma Sarah.

Yes, it’s a new Jewish text.

And yes—it’s good for the Jews.

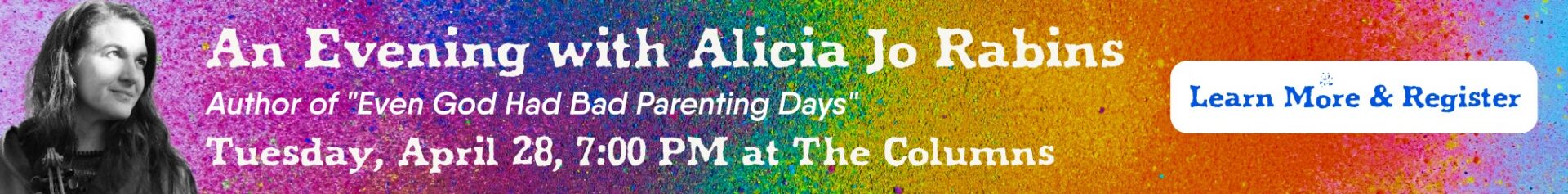

My podcast partner, Melissa Hunter, and I talk about all this and more The Kibbitz. You can listen by clicking right here.