TREBLINKA, Poland — In 1998, after visiting the Treblinka death camp site on a Holocaust education trip to Poland for teachers, Aimee Ross vowed she would never come again.

“I knew enough about it to know how horrifying the property was…as I was walking around, it felt so eerie to me,” Ross said.

The Treblinka visit was at the end of an intense week, where Ross and her group of roughly 50 other teachers had also visited Auschwitz and Majdanek. Walking around the Treblinka memorial — a clearing in the woods with jagged rocks sticking out of cement, with the names of murdered Jewish communities listed on larger stones — Ross was exhausted.

She was struck by the fact that while Auschwitz and Majdanek were preserved as museums, Treblinka had been completely destroyed by the Nazis to hide the evidence of mass murder. As a result, to Ross, the land held much more unrest.

“I was very much missing my two daughters, who were four and six,” she said. “But I just remember [feeling like] I don’t really need to walk around very much here. I get it. I see what the jagged rocks are and what the memorial is about.”

Aimee Ross (wearing blue, on left) on a day trip with the JCRC group to the small Polish town of Czyzew (Lev Gringauz/TC Jewfolk)

But almost 26 years later, this past Wednesday, Ross proved herself wrong: She did come back to Treblinka, this time with 15 other teachers on the Power of Place trip run by the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota and the Dakotas. The trip is a joint venture with Humanus Network, a Holocaust education consulting organization.

The unexpected return prompted Ross to reevaluate her sense of the place, and how to teach students and inform others about it in her rural north-central Ohio community. Ross came on the trip with the help of a grant from the Ohio Holocaust and Genocide Memorial and Education Commission.

“I’m processing, in a way, for audiences already,” she said. “How am I going to bring this out to the audience so that it makes sense, so that they can learn through my experience? So it’s not just the teaching angle.”

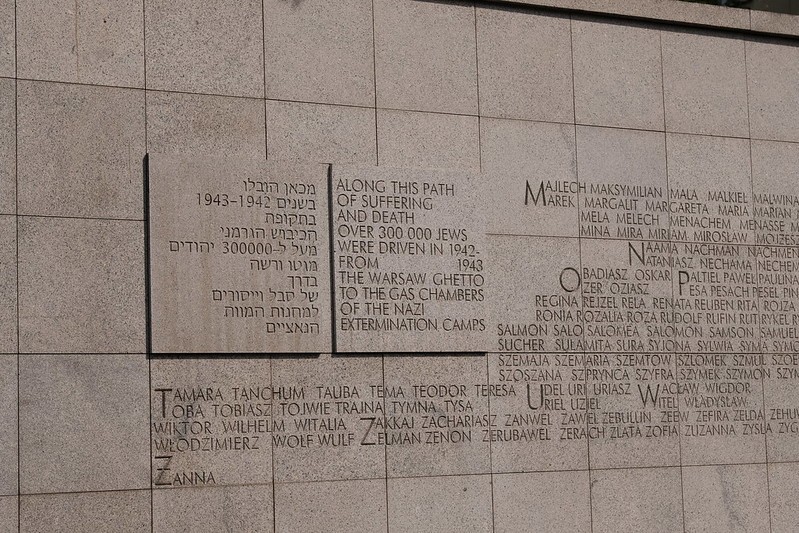

First, though, came the Warsaw Ghetto. As the JCRC group continued its tour on Wednesday morning, one of the first stops was the site of the Umschlagplatz, the deportation point from which over 300,000 Jews were shipped from the ghetto to their deaths at Treblinka. But the group also learned about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, visiting a site of a destroyed bunker that served as a mass grave for many Jewish resistance fighters.

Part of the inscription on the Umschlagplatz memorial in Warsaw (Lev Gringauz/TC Jewfolk)

“The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising has become much more significant to me than it ever was before,” Ross said. “All of a sudden, there’s a lot of things that are happening here for me, in terms of, how do you want to teach moving forward, and maybe focusing on the ghetto?”

Ross also had a unique moment, asking the tour guide, Jola Wojciechowska, if a building on the other side of the road from the Umschlagplatz memorial had been there during the time of the ghetto. After all, it seemed to appear in old photos of the ghetto. Yes, Wojciechowska replied – in fact, that building used to be the SS headquarters in Warsaw.

Understanding the connection between the ghetto and the camp brought new clarity for Ross, and helped reframe the visit to Treblinka from being simply overwhelming to an educational tracing of the path taken by the victims of the Holocaust.

During the 90-minute drive from Warsaw to Treblinka, Ross tried “to do all the things that I didn’t do [in 1998], like pay attention to the countryside and pay attention to the towns that we go through,” she said, really absorbing the sense of place.

Once the JCRC group arrived, they entered a small building that houses a museum with a model reconstruction of the layout of the camp. A series of short videos, with survivor testimony, made clear the purpose and scope of the death camp.

Set up in 1942 as part of the Nazi’s secret plan for the extermination of all Jews, Treblinka was a new, ruthlessly efficient way to mass murder people without wasting too many bullets by using shooting squads. Instead, groups of Jews were packed into sealed bath houses where carbon monoxide gas from an engine exhaust poisoned and suffocated them within 20 minutes.

A fake hospital with a red cross flag also hid an execution area and mass grave. Altogether, over the course of about a year, almost 1 million Jews were murdered here, while the Nazis played a sick deception: The Treblinka train station sign had made up arrival and departure times, implying that it was simply a layover point, and the path to the gas chambers was called “the road to heaven.”

The stone commemorating people from Warsaw — overwhelmingly, Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto — murdered at Treblinka. One small rock on the commemorative piece, left by a visitor, reads “Golda” (Lev Gringauz/TC Jewfolk)

After the museum videos, and seeing the few remains of the camp excavated — a piece of gas chamber foundation, bits of bath house tiles and decorative crosses, a handful of buttons and trinkets left by the dead — the group walked to the actual location of the camp and its memorial.

Instantly, Ross remembered her 1998 trip as she felt the damp summer smell of the forest carried on a persistent breeze.

“It just took me back to that moment where I said I’m never coming back here again,” Ross said. “But oh my God, here I am — and it made me very emotional, [asking herself] what are you doing here again?”

But this time, 26 years later, Ross could think more clearly about Treblinka.

“It became more about thinking of the victims, and the people who had no idea where they were going and being lied to,” she said. “It wasn’t about being depressed after a week of finding out information, and being a sad mom…but it was more about the ‘holy shit’ moment of what humanity did.”

Ross has a PowerPoint she uses to teach about Treblinka to her students, and now she plans to restructure it into a similar approach taken by the JCRC group: Learning about the Warsaw Ghetto, and then studying Treblinka in context of the larger picture of how the Nazis engineered the Holocaust.

What happened here is an incredulous thing to consider, and prompts a litany of haunting questions — including, for Ross, what feels like a strangely logistical but important question: Where did all the belongings of the murdered Jews go? The museum videos said clothing was shipped back to Germany, and that around $750 million worth of goods were stolen from the death camp’s victims.

Susie Greenberg, associate director of Holocaust education at the JCRC, lights a memorial candle held by teacher Charlie Grossman during a ceremony at Treblinka (Lev Gringauz/TC Jewfolk)

“How do you just start shipping that to Germany?” Ross asked. “And who’s receiving it?”

That’s a kind of question that opens the door to learning about yet another dimension of the Holocaust, and the disturbing reality of how the culpability for destroying Jewish life goes far beyond the Nazi soldiers who operated the death camps.

The JCRC group did a small remembrance ceremony in Treblinka, lighting memorial candles and reading a version of the Mourner’s Kaddish prayer that includes a recitation of various concentration and death camps.

The Treblinka death camp memorial site from the back of the forest clearing, now with the sun out (Lev Gringauz/TC Jewfolk)

At the end of the ceremony, the sun suddenly came out and chased away the overcast clouds, giving the group a sense of wonder and a measure of relief — a sign from God, or simply a coincidence? In a place like this, amid acts like these, it’s never clear.

Afterward, the teachers wandered the memorial, taking in the clearing, the stone, the strange beauty of the forest at rest, and the heaviness of the place.

The visit to Treblinka continues to simmer with the trip participants.

“Today was kind of a reality check…the Nazis were such a machine: ‘Okay, this didn’t really work. Let’s try this. Let’s get this done’…because how many places had they already been killing by the time they got to Treblinka,” Ross said.