Beginning

I didn’t wake up the morning of June 2nd thinking my life would change. I woke up jet-lagged, sunburned, exhausted (having just returned from my first cruise the day before), and excited for my first pride event of the month. I was tabling at Northern Kentucky Pride with the Cincinnati Pride table.

About halfway through the event, a group wearing knit watermelon hats came up next to us with a table and a cart and started setting up a booth. I saw the sticker in the corner of their table, labeled Cincinnati Socialists.

They had not paid to be there (they did not have a tent or a set space; the group had pulled a cart up halfway through the event and set themselves up), and they were handing out pamphlets titled “Netanyahu’s Final Solution,” which uses a trope called Holocaust Inversion and trivializes the trauma of the Holocaust. In other words, it was a textbook case of antisemitism.

When this was pointed out to the Socialists, they replied, “It’s not antisemitic because we are Jewish.” Holding an identity does not mean that you cannot hold internalized bigotry. There are plenty of examples of internalized homophobia, internalized racism, and internalized ableism. The core of internalized bigotry towards identities that one holds is the shame for one’s own identity.

The NKY Pride organizers promptly asked the Socialists to leave because they had not paid to be there.

Fallout

Over the next week, the Socialists and another group called DivestCinciPride posted photos and information on Instagram about my involvement in the institutional Jewish community. They weaponized it to shame my relationship with Israel as a Jewish person publicly.

Their behavior amounted to publicly shaming me specifically for being Jewish. Later, there were folks who said it wasn’t my Judaism but that I was a Zionist. They assigned an identity of Zionist to me and never actually asked me if it was my belief system. I was called a Nazi for having a relationship with Israel, and somehow that wasn’t recognizable to these folks as antisemitism.

The overwhelming majority of modern Jews have some form of relationship with Israel, and publicly shaming them for that isn’t advancing the cause of Palestinian rights – it’s just being antisemitic. To that end, my relationship with Israel is deeply personal, incredibly complicated, and not relevant to this argument.

Even more problematic, these groups implied that being what they perceived as a “Zionist” meant that I was unqualified to be the Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The notion that one cannot be a DEI professional because they’re Jewish ignores every other identity they hold – in my case, as a disabled trans person. Their argument also ignores all of the DEI and antiracist work I’ve done in my life.

Things only got crazier and scarier from here.

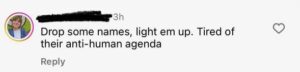

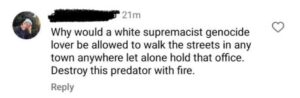

Unknown individuals made direct threats to me and my family, and I had to make police reports and FBI phone calls. Anonymous individuals harassed me, focusing especially on the fact that I participated in a national march against antisemitism. After all this was over, some people (including the Socialists) tried to say there weren’t threats of violence. The gaslighting of a marginalized person’s safety is infuriating and the exact opposite of social justice.

My spouse and I went out and bought a Ring doorbell to track who was coming and going from our home. We don’t have our mezuzot up, but now we have a Ring doorbell because public displays of Judaism are inherently dangerous.

At the core of this situation is the sad fact that these groups see every part of their argument as black and white. Either you support the state of Israel, or you are against it. If you are Jewish, you are either anti-zionist or Zionist – and if you’re a Zionist, then you are a part of the monolith that supports the ultra-far-right government of Israel. There is no nuance as to the rights of Palestinians. They take every ounce of critical thought out of the argument to say that my Jewish identity (including a relationship with Israel) means that I support the horrific human rights crisis going on in Gaza.

- screenshots of comments, dms, posts, and stories

Secondary Trauma

Enough people piled on in this antisemitic experience that members of the Cincinnati Pride Board of Directors asked me to resign from my position. The Pride Board had been getting criticism for having a “Zionist” as their DEI Director, and certain members felt it would be better for the organization if I were no longer involved.

The worst part about all of this is that the extremists won. The people who told me to be ashamed didn’t actually succeed in making me ashamed, but they made people around me ashamed enough to cast me aside. People I trusted turned their backs on me. I had to leave the Board of Directors for an agency I served for three years.

Adding insult to injury, it quickly became clear it would be physically unsafe for me to celebrate Pride or attend any Pride events due to the way people personally threatened me. There were plans made to put my face on posters and directly protest my involvement in the LGBTQ community, as what they described as a “Zionist.”

People have told me these aren’t threats, that I’m being dramatic, or even that visible Zionism has no place in Pride. They have also sought to say that “merely calling out genocide” isn’t antisemitism or harassment, but apparently, my existence as a Jewish person is transgressive.

Hundreds of people piled on, with many I didn’t know telling me to feel shame for something I didn’t do and had no control over. One relatively insignificant but very sad result was that the LGBTQ Jewish organization I run had to cancel our Pride event for safety concerns. Worse yet, I couldn’t even tell people why.

I feel like I lost everything I worked for in the span of a single week.

Rebuilding

The whole situation is deeply personal because it’s about my own identities and feelings, but also, it’s so much bigger than any part of me, and one experience could not contain the multitudes of different emotions I feel and needs I have.

People keep telling me they’re sorry but apologizing for something they didn’t do. People keep asking me what they can do to help and support me, but at this point, I have to sit with this trauma by myself and try to heal while being a symbol for the broader Jewish community.

I spent the day of Pride out of the state. I kept checking social media to make sure nothing horrible happened. I was terrified of seeing violence and of seeing protest posters with photos of my face (a real threat if I hadn’t resigned).

National news organizations have published information about my situation, and people I don’t know suddenly know me, my story, and my struggle. One bright spot was the Jewish community stepped up and put their arms around me in a way I never imagined.

Beyond being supportive, I hear again and again that my Cincinnati Jewish community is also angry on my behalf. They put so much work into LGBTQ inclusion and belonging and were met with antisemitism. In dealing with my own trauma, I found I wasn’t prepared for what it meant to become a symbol of intersecting identities.

Thankfully, there are folks to do the rebuilding work on my behalf so that I can focus on working through these emotions instead of leading from a place of trauma. Thankfully, a few weeks have passed since an account last posted my photos, and no new threats have come my way. Thankfully, the Pride Festival and Parade (and separate Jewish community service) went on without huge public issues.

In reflecting on this whole situation, I now have to internalize how public displays of Judaism – or even just being Jewish publicly – might be more dangerous than it has been in the past. However, we, as a Jewish community, aren’t backing down. The public shaming might have worked this first time, but I know the symbolic bullet I took on behalf of the Jewish community won’t be in vain.

I refuse to be ashamed of my identity, and I refuse to apologize for standing up against hatred. I also refuse to say that believing in a state of Israel of peace, justice, and prosperity for all the inhabitants is somehow wrong, something to be ashamed of, or somehow antithetical to DEI. I know my voice matters to someone somewhere, and I will keep being my authentic self for the next person like me.

Sending you so much love and support, Elliot. Thank you for continuing to share your story.

We indeed live in sad times when ignorance and misinterpretation of history and culture have stronger influence on the public and community groups!!!

Continue to find the internal strength to work past this hatred, harassment and bigotry!! May others in our community continue to promote the work you have been accomplishing for some time to enrich our lives.